Despite Economic Woes, the Book Fair is Bigger Than Ever

Thomas George

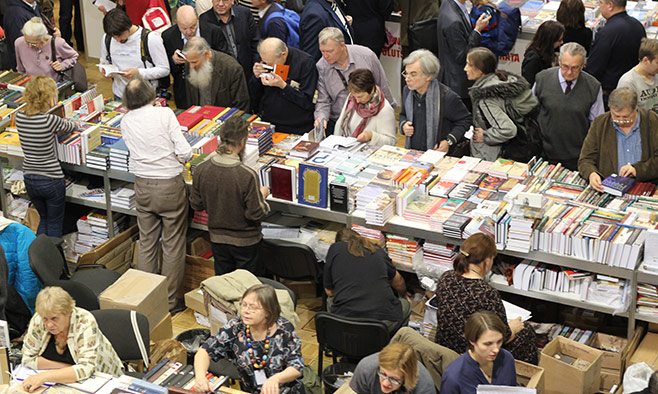

Unlike other book fairs around the world, the Non-Fiction Fair is primarily for readers, not store buyers or publishers. Sergei Golovko / MT

Other countries have book fairs where publishers come to do business. The 17th International Book Fair for High-Quality Fiction and Non-Fiction — commonly simply referred to as "nonfiction" — taking place in Moscow this week is very much an event for readers. And as such it is a good place to find out how Russian reader tastes are changing, and how publishing houses are struggling to satisfy those tastes — and stay afloat.

In addition to the long-winded authors and emoting poets who typically get top billing at any book fair, "non/fictioNo17" has a broad appeal for all types of visitors: from parents looking for books to help raise their children as independent thinkers to adults seeking cook books or a photo op with an Ecuadorian Indian princess. All this under one roof at the Central House of Artists.

From the opening press conference it became clear that the publishing industry is in the process of surviving a car crash, and, looking down at its scratched and bruised body, is pleasantly surprised to see it's still alive.

"We publishers are amazed at our own existence," said Irina Prokhorova, a member of the expert committee of the fair and chief editor of NLO Publishing. "The book industry survives thanks only to small independent publishers —they are the basis for the continuation of culture for the country."

Despite grumbling about economic hardship and limited government support, the fair has a festive and cozy feeling. "I've been at 16 of these fairs. It's like coming home and seeing old friends," said Marina Dyadunova, marketing manager at VES MIR Publishing.

There are 274 publishers in attendance — 25 more than last year. Spanish language and literature is playing the role of "Guest of Honor," with 19 authors from 8 Spanish speaking countries present. Other countries with stands include France, Poland, Germany and Japan. The US Embassy planned to have a stand as it has in past years, but cancelled at the last minute.

"The fair provides a great opportunity for readers to fill their shelves with a broad selection of books, often at discount prices," said Julia Blagorazumova, the fair director. There are two stands with English language books, and even a hall dedicated to selling old-style LP records, as the vinyl crave hits Russian music-lovers.

Oleg Klevnyuk's new biography of Josef Stalin is one of the year's most anticipated books.

Sergei Golovko / MT

Thinking Tots

Children's literature and development is a paramount theme at fair, under the motto "Think for Yourself!"

"Today we live in a society where infantile thinking, indifference and zombification of the individual can have frightening consequences for society as a whole," according to the fair press release. To counter this, the event offers a developmental interactive quest for children. "It's an effort to battle the absence of critical thinking," said Anna Tikhomirova, a child psychologist and president of the Childhood Culture foundation. There are also special sections with books for those contemplating adoption and for teenagers, she added.

There is a "Discovery Zone" for children, where they can participate in seminars, developmental games, history discussions and illustration classes.

A near stampede towards the children's publisher stands on the third floor just after the fair opened Wednesday afternoon confirmed that nothing gets in the way of a Russian mother trying to obtain something for her child.

Hopefully some of those aggressive moms will purchase a very unique book that debuted at the fair. Far deeper than Suessian rhymes like "one fish, two fish, red fish, blue fish," "The ABC's of Truisms," is a unique volume from Clever Publishing that has 33 stories by 33 famous Russian authors—one for each letter of the Cyrillic alphabet. The stories describe important values to young readers, like "a" is for avtoritet (authority) and "b" is for byt (existence).

The fair has a section for supervised children's activities, so that parents can wander the book stalls at leisure.

Sergei Golovko / MT

Business for Grown-Ups

People working in the publishing industry, especially those dealing with foreign literature, have little time for such philosophizing, though clinging to their values seems to be a common theme of success in time of crisis. The litany of problems plaguing publishers left some feeling squeezed and others defiant.

Varvara Gornostayeva, a member of the fair's executive committee and chief editor at Corpus Books — a publishing house with a reputation as a leader in foreign literature in Russia — is counting on her company's reputation and instinct to keep them successful.

"We are under pressure from "mass" literature publishers, which have huge print runs. But we are defending our position and our reputation as a publisher of high-quality literature. We have some popular books that have 80,000 to even 150,000 print runs. But for our average book, if we sell 3,000 we are satisfied," she said. Gornostayeva, who brought Steve Job's memoir here and is just now introducing the memoir by Monty Python's Terry Gilliam to Russian readers, is an optimist. "Despite the crisis and the typical Russian tendency to complain, things are going well for us. Though prices of books are going up while book-buyer's salaries are not, we are counting on our readers. So far it's working."

Oleg Zimarin, general director and editor-in-chief at VES MIR Publishing, which handles a mix of Russian and foreign academic, history, and international relations books — including this author's book — sees a shrinking market for scholarly works. One tool he uses is funding from foreign government and public organizations which help pay for translation and printing costs. "That means that publishers very often don't publish what they want but choose books which get external support," Zimarin said. "This creates a strange and misleading picture of translated books on the market."

Text Publishing is another company with a focus on foreign literature. It started out publishing local legends like the Strugatsky brothers and has expanded to translations of western writers, like Samuel Beckett, Isaac Singer and others. But buying foreign rights in hard currency with a weakened ruble is problematic. "The ruble crash has had a big impact, while at the same time it's impossible to raise prices — it would just put an end to book buying," said Olgert Libkin, head of Text. He also laments distribution shortcomings, like the absence of real chain-stores or discounts from Russian Post for book mailing – a move that would buoy Internet book sales.

Lovers of vinyl will find plenty to buy. Sergei Golovko / MT

Government Support, Sort Of

If the publishing industry car is crashing, the airbag of government support has yet to fully deploy. Fair organizers were thankful they got agreement from the Moscow City Government to waive a new trade levy that would have seen each stand owner fork over 80,000 rubles to the government, on top of what they were already paying for their stands. But they lamented the fact that in the federally declared "Year of the Book," city governments around the country were closing down bookstores and libraries.

VES MIR's Zimarin has seen signs of support at the federal level. The government press agency Rospechat helped finance printing of some of his foreign titles. The only long term cure for the Russian publishing industry's woes is a breakthrough in e-books, Zimarin said. This must be accompanied by serious enforcement of intellectual property rights legislation.

"E-pirates should be considered as terrorists who are a threat to national security," he added. And he believes that there are best practices worth mimicking. "VAT for books in the UK is zero; the Norwegian government buys a thousand copies of every title published and their average prices are ten times higher than in Russia. This kind of approach could return vitality and influence to Russian publishing. That would be for good of society as a whole."

This year the antique book section is larger than ever. Sergei Golovko / MT

Evolving Tastes

Meanwhile, publishers of foreign literature have to keep up with evolving reader preferences in order to maximize their share of limited disposable income. There is overall agreement that nonfiction is outpacing fiction, though modern classics remain popular. And there is little room for unknown foreign authors, while domestic writers are gaining ground.

"We see that interest towards foreign authors writing about Russia is steadily decreasing," said VES MIR's Zimarin. "There was a great boom in 90s. The first volume of American historian Robert Tucker's biography of Stalin sold more than 100 thousand copies in 1990 and only one thousand of the second volume in 1996."

Corpus's Gornostayeva credits the growth of sales of popular science books – like the works of Richard Dawkins and Eric Kandel – to the efforts of Dmitry Zimin's Dynasty Foundation, which closed recently because he refused to accept the label of foreign agent.

"There was a similar genre during Soviet Times, but it fell apart when the country did, and was only resuscitated thanks to Dynasty," she said. "In the 12 years that they worked, their book program not only financed scientific works, but they also had an expert committee that helped to select books, and they funded qualified scientific editors to help make a high-quality final product."

Gornostayeva sees the share of Russian authors growing not only in non-fiction, but also fiction. "After the breakup of the USSR we were starving for foreign literature — any author, any language — and demand was huge," she said. "But ten years later there was saturation and readers became more discriminating. So in fiction we focus now only on big important projects: where popularity is matched by quality. Like Donna Tartt's The Goldfinch. We are not talking about works like Fifty Shades of Grey."

Sometimes she makes decisions about what book rights to buy based purely on instinct. "We enjoyed the Terry Gilliam memoir ourselves so much that we bought the rights without giving it a second thought. We just believe, based on our experience, that it will be liked by our readers," Gornostayeva said.

"It fits the accepted business model of successful independent publishers: having one track with proven, reliable products so we can be sure of the return on investment, and another line of more exotic projects where we operate on gut feeling and take risk," she added.

The foreign authors that Text Publishing seeks are also those who are already well known in their home countries. "Rarely do we deal with new authors," said Text's Libkin. "However the spectrum of languages we are interested in is very broad: from Chinese (Yu Hua) to French (Modiano) to Hungarian (Kertesz)."

But clearly Libkin is not in this business in order to get rich.

"The German poet Heinrich Heine said that he became a poet because his mother liked to read poetry, while his rich uncle became a banker because his mother liked books about thieves," he said. "I suspect my mother did not read books about thieves."

Central House of Artists. 10 Krymsky Val. Metro Park Kultury and Polyanka. +7 495 657 9922. moscowbookfair.ru. Wed. 2-7 p.m., Thurs. through Sun. 11 a.m. to 7 p.m.

Contact the author at artsreporter@imedia.ru